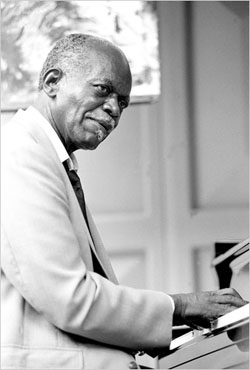

Hank Jones, Versatile Jazz Pianist, Dies at 91

Hank Jones, whose self-effacing nature belied his stature as one of the most respected jazz pianists of the postwar era, died on Sunday in the Bronx. He was 91.

Hank Jones, whose self-effacing nature belied his stature as one of the most respected jazz pianists of the postwar era, died on Sunday in the Bronx. He was 91.

His death, at Calvary Hospital Hospice, was announced by his longtime manager, Jean-Pierre Leduc. Mr. Jones lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and also had a home in Hartwick, N.Y.

Mr. Jones spent much of his career in the background. For three and a half decades he was primarily a sideman, most notably with Ella Fitzgerald; for much of that time he also worked as a studio musician on radio and television.

His fellow musicians admired his imagination, his versatility and his distinctive style, which blended the urbanity and rhythmic drive of the Harlem stride pianists, the dexterity of Art Tatum and the harmonic daring of bebop. (The pianist, composer and conductor André Previn once called Mr. Jones his favorite pianist, “regardless of idiom.”)

But unlike his younger brothers Thad, who played trumpet with Count Basie and was later a co-leader of a celebrated big band, and Elvin, an influential drummer who formed a successful combo after six years with John Coltrane’s innovative quartet, Hank Jones seemed content for many years to keep a low profile.

That started changing around the time he turned 60. Riding a wave of renewed interest in jazz piano that also transformed his close friend and occasional duet partner Tommy Flanagan from a perpetual sideman to a popular nightclub headliner, Mr. Jones began working and recording regularly under his own name, both unaccompanied and as the leader of a trio. Listeners and critics took notice.

Reviewing a nightclub appearance in 1989, Peter Watrous of The New York Times praised Mr. Jones as “an extraordinary musician” whose playing “resonates with jazz history” and who “embodies the idea of grace under pressure, where assurance and relaxation mask nearly impossible improvisations.”

Mr. Jones further enhanced his reputation in the 1990s with a striking series of recordings that placed his piano in a range of contexts — including an album with a string quartet, a collaboration with a group of West African musicians and a duet recital with the bassist Charlie Haden devoted to spirituals and hymns. In 1998, he appeared at Lincoln Center with a 32-piece orchestra in a concert consisting mostly of his own compositions.

Henry W. Jones Jr. was born in Vicksburg, Miss., on July 31, 1918. He grew up one of 10 children in Pontiac, Mich., near Detroit, where he started studying piano at an early age and first performed professionally at 13. He began playing jazz even though his father, a Baptist deacon, disapproved of the genre.

Mr. Jones worked with regional bands, mostly in Michigan and Ohio, before moving to New York in 1944 to join the trumpeter and singer Hot Lips Page’s group at the Onyx Club on 52nd Street.

He was soon in great demand, working for well-known performers like the saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and the singer Billy Eckstine.

“People heard me and said, ‘Well, this is not just a boy from the country — maybe he knows a few chords,’ ” he told Ben Waltzer in a 2001 interview for The Times. He abandoned the freelance life in late 1947 to become Ella Fitzgerald’s accompanist and held that job until 1953, occasionally taking time out to record with Charlie Parker and others.

He kept busy after leaving Fitzgerald. Among many other activities, he began an association with Benny Goodman that would last into the 1970s, and he was a member of the last group Goodman’s swing-era rival Artie Shaw led before retiring in 1954. But financial security beckoned, and in 1959 he became a staff musician at CBS. He also participated in a celebrated moment in presidential history when he accompanied Marilyn Monroe as she sang “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy, who was about to turn 45, during a Democratic Party fund-raiser at Madison Square Garden in May 1962.

Mr. Jones remained intermittently involved in jazz during his long tenure at CBS, which ended when the network disbanded its music department in the mid-’70s. He was a charter member of the big band formed by his brother Thad and the drummer Mel Lewis in 1966, and he recorded a few albums as a leader. More often, however, he was heard but not seen on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and other television and radio programs.

“Most of the time during those 15 or so years, I wasn’t playing the kind of music I’d prefer to play,” Mr. Jones told Howard Mandel of Down Beat magazine in 1994. “It may have slowed me down a bit. I would have been a lot further down the road to where I want to be musically had I not worked at CBS.” But, he explained, the work gave him “an economic base for trying to build something.”

Once free of his CBS obligations, Mr. Jones began quietly making a place for himself in the jazz limelight. He teamed with the bassist Ron Carter and the drummer Tony Williams, alumni of the Miles Davis Quintet, to form the Great Jazz Trio in 1976. (The uncharacteristically immodest name of the group, which changed bassists and drummers frequently over the years, was not Mr. Jones’s idea.)

Two years later he began a long run as the musical director and onstage pianist for “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” the Broadway revue built around the music of Fats Waller, while also playing late-night solo sets at the Cafe Ziegfeld in Midtown Manhattan.

By the early 1980s, Mr. Jones’s late-blooming career as a band leader was in full swing. Since then he worked frequently in the United States, Europe and Japan. While he had always recorded prolifically — by one estimate he can be heard on more than a thousand albums — for the first time he concentrated on recording under his own name, which he continued to do well into the 21st century.

He is survived by his wife, Theodosia.

Mr. Jones was named a National Endowment for the Arts jazz master in 1989. He received the National Medal of Arts in 2008 and a lifetime achievement Grammy Award in 2009. And he continued working almost to the end. Laurel Gross, a close friend, said he had toured Japan in February and had scheduled a European tour in the spring until doctors advised against it. He was also scheduled to perform at Birdland in Manhattan this summer to celebrate his birthday.

Reaching for superlatives, critics often wrote that Mr. Jones had an exceptional touch. He himself was not so sure.

“I never tried consciously to develop a ‘touch,’ ” he told The Detroit Free Press in 1997. “What I tried to do was make whatever lines I played flow evenly and fully and as smoothly as possible.

“I think the way you practice has a lot to do with it,” he explained. “If you practice scales religiously and practice each note firmly with equal strength, certainly you’ll develop a certain smoothness. I used to practice a lot. I still do when I’m at home.” Mr. Jones was 78 years old at the time.